Welcome to our calendar of environmental events in Chester County. To submit an event click here. If you can’t see events below, go here. The most convenient view (click upper right icon) is Schedule.

Pielli’s bill to protect native species passes PA House

We all know how important insects and other invertebrates are, for their role in ecosystems (such as pollinating flowers, fruits and vegetables), because of their importance in the food chain (think of many birds’ menus), and because some of them are so pleasing to the human eye (e.g., butterflies!).

Now Rep. Chris Pielli of the 156th PA House district, in the West Chester area, has proposed a bill to add “wild native terrestrial invertebrates” to the flora and fauna already protected under the 1982 Wild Resource Conservation Act.

The bill authorizes the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources to gather appropriate research and take necessary measures to protect rare and endangered species.

Now the PA Senate needs to act favorably on the bill. Read more here and see the full text here.

Everybody has to take action’ against Climate Change

‘Everybody has to take action’ is a locally-sourced article, including several CCEA-connected individuals, in the Chester County Press, 12/25/2024, by Gabbie Burton.

Jim Wylie, conservation co-chair of the Sierra Club’s SEPA Group, stressed the impacts of flooding:

“I’ve seen the infrastructure be stressed, particularly, bridges over swollen creeks and part of that is due to over development, having less permeable surfaces and having more stormwater runoff when it starts to rain hard. But some of it’s also the intensity of the storms, number of inches of rain per hour that gets dropped.”

You can read the full article here. Below, graphic published in the article, from Friends of the Earth.

Environmental Justice

Environmental Justice (EJ) is a vital issue that takes us beyond environment. People have caused environmental degradation and social inequality, just as they have caused disparities in medical treatments and health treatment outcomes. Thus people alone can solve the resulting problem of wealthier people generally having everyday access to better environmental conditions and resources than those less socioeconomically fortunate. The key to change is, as always, grassroots action and community involvement, which in turn educate public officials and lock in progress.

As the Pennsylvania Constitution (I.27) proclaims, environment is for “all the people”:

“The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.”

The following information is adapted from a presentation by Maurice Sampson II at the January 27, 2024, meeting of CCEA and subsequent discussion, including his outline of the main concepts:

Chester County, prosperous though it is overall, has its own EJ areas. Historically in our society, toxic manufacturing and processing facilities have always been concentrated in minority areas.

The PA Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) revised its Environmental Justice policy in 2023 and has developed PennEnviroScreen to evaluate the environmental burden of communities. High scores, based on both environmental and socioeconomic factors, designate EJ areas. In those areas the community is currently allowed to be involved in the permitting process for proposed facilities, but that means participation in discussion not in decision-making.

PA House Bill 652, under consideration in Harrisburg, provides more of a mandate, requiring every permit to take into account cumulative impact, rather than allowing development to proceed as if there is no other pollution already in place in the area. Under this bill, DEP could reject applications based on community participation and cumulative impact. See more on HB 652 here. Organizations for Pennsylvania’s Environmental Justice Bill HB652 includes a letter of support that organizations are invited to endorse; individuals can sign on here.

Chesco currently has 5 EJ areas with scores over 80: Modena 97, Valley Twp 95, Honey Brook Twp 87, N. Coventry Twp 84, Coatesville 80. And just behind those, in the 70s: Penn Twp and Sadsbury Twp 79, Oxford Borough 78, New Garden Twp 74, West Chester Borough 73.

This EnviroScreen model combines pollution burden, health, and demographics to identify EJ areas. Underlying info includes pipelines and other environmental factors, plus social factors like poverty and race. But ratings are not only for Black and Brown people; the tool raises standards for all areas and issues. We can’t solve these problems from the top down, but need to start within the communities. We need to talk to people in place and go to their meetings. The poor have the intellect and understanding of the problem but they lack the resources and political clout to solve the problem on their own.

After Maurice’s presentation, others added further info. POWER is actively addressing environmental justice in Phila and Bucks, Montgomery, Delaware, Chester and Lancaster counties. Its Climate Justice & Jobs team meets regularly; see info posted on our site here. Their branch called POWER Metro focuses on the Philly suburbs. See also the PA Dept of Health’s Environmental Justice Strategic Plan, connecting environmental justice and health equity.

The Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed concluded from a discussion with EPA that no community is too small to be focused on. Modena (southeast of Coatesville) has the lowest score in Chesco; we need volunteers to find out what is being done there to help. Every neighborhood has people and organizations that love their neighborhood and would never leave it, and EJ areas are no exception. Working on Environmental Justice in Chester County will require finding and building relationships and working in alliance with community organizations (not necessarily environmental ones) in the impacted municipalities.

EPA’s web site has an EJ section including a geographical microdata tool, that helps link health to contamination. An EJ conference is in the planning for 2025, with the objective of building a next network of Environmental Justice organizations.

POWER Interfaith

by Kathy McDevitt

POWER Interfaith is “a grassroots organization of Pennsylvania congregations and individuals committed to racial and economic justice on a livable planet.”

I attended the excellent POWER interfaith team meeting on Jan. 30, 2024. One of their five focus areas is Climate Justice. Below are slides of their accomplishments and goals in the climate justice area. They could definitely be strong allies for those of us working in that field.

The Plastics Problem in PA and everywhere

Single-use bag ban in your community

Is your community considering a ban on single-use plastic bags? There are many advantages: cutting down on litter (which has to be picked up or it disfigures nature, reducing use of fossil fuel (from which plastic is made), reducing costs to businesses and consumers (someone has to pay for those throwaway bags), and reducing costly shutdowns to clean recycling equipment gummed up by bags.

How many plastic bags a year would be saved in your community, based on population? See Environment America’s Single-use Plastic Bag Ban Waste Reduction Calculator. (It’s based on population, at the rate of about 300 bags per resident; the tool takes a while to load; enter just the municipality, not state.)

What other factors need to be considered? See many resources at PennEnvironment, including a model ordinance.

What are the answers to some common issues that may arise as public officials consider a ban? Here are some points from a 12/31/22 memo from Maurice M. Sampson II of Clean Water Action to members of Philadelphia City Council as they considered strengthening the established ban by levying a fee of $.15 on all bags, whether plastic or paper. Download the 5-page memo here.

• Why is a fee for single-use carry-out bags necessary?

Experience shows that a straight ban on throwaway plastic bags multiplies the use of throwaway paper bags, which are more expensive. The most equitable solution is to add a flat fee for all bags a consumer uses to that consumer’s bill. Savings to the business from not having to buy and give away bags can be passed on to consumers. Consumers rapidly learn to carry their own reusable (and more resistant) bags.

• What is the impact of bag fees on low-income residents?

Studies show that low-income people adjust their behavior just like anyone else. Any exceptions to the fee would prevent businesses, whether large or small, from saving the cost of bags and would fail to reduce litter and environmental impacts locally.

Scary fact: every American consumes an average of almost one single-use plastic bag a day! Please try to make every day a day without a throwaway bag! And of course, never go shopping without the needed number of reusable bags.

Cutting plastic waste

Moving forward with the Chester County Single-Use Plastic Bag Ban Coalition! More info here.

Economics of Single Use Plastic Bags (Easttown EAC, 2022)

[download pdf here]

During the February 22nd, 2022, meeting, the EAC’s single use plastic bag ordinance was initially presented to the Board of Supervisors. Following the presentation, the Supervisors asked for further information regarding the economics of single use plastic bag bans. The following is a summary of information to meet that request.

In general, single use plastic bags are economically problematic because they are derived from fossil fuels, are a source of litter on land and water, create tangles and jams in recycling and wastewater processing equipment and prove costly to municipalities in terms of time and money to manage. Most of the economic data currently available focuses on the economic costs of plastics rather than the savings associated with bag bans. However, there is supportive data regarding the role of bag bans and businesses/business owners.

For business owners, removing plastic bags from the list of supplies businesses require saves them money in the long run. Currently, single use plastic bags are offered to customers free of charge and are a cost business owners must account for in their pricing for goods and services. While the per unit purchasing cost of paper bags is higher than that of plastic bags ($0.15 versus $0.01) the proposed ordinance requires customers to pay for paper bags ($0.15 fee) so businesses can recoup these costs.

Prior to the statewide plastic bag ban in CA, San Francisco’s Office of Economic Analysis found the following: ‘Their models predicted a “slight positive impact on the local economy” due to the overall decrease in bag-related costs post-ordinance, and to the economic multiplier effects that could occur alongside the projected increase in consumer spending associated with decreasing product costs passed on by retailers. The same study reported that impacted San Francisco retailers would enjoy a savings of $3 million over the course of a year under the strengthened ban, due to the forgone purchasing costs of single use bags.1

Additionally, with the proposed ordinance, businesses will be given a 90-day transition period during which they can utilize their existing supply of plastic bags without risk of penalty. The length of this transition period was determined based on the findings of the business community survey conducted in Easttown Township during the fall of 2021.

Beyond local businesses, plastic pollution in costly to local municipalities, utilities, and services. Penn Environment states, “Bags are an economic burden on local governments and taxpayers, with millions of dollars in hidden, externalized costs.”2For example, the Clean Air Council of PA has estimated the production stream costs (from fracking to being thrown away) of plastic bags to be between $20-$30 per year for Philadelphia taxpayers. Removing these bags from a municipality ultimately removes this cost for the tax base.3

Within Philadelphia, the Water Department is spending heavily to pull litter out of sewer drains and other stormwater infrastructure. They estimate that plastic pollution is doubling the maintenance costs of their green stormwater infrastructure, requiring 32 dedicated cleaning crews to remove items from their infrastructure. In 2017, city crews removed 67 tons of debris from their stormwater system, much of it being single use plastics. It bears repeating, cleaning up this litter comes with additional costs to users.4

Furthermore, “a recent study by Keep Pennsylvania Beautiful estimated Pennsylvania spends $48 million a year to clean up litter. The report included an estimate that PennDOT spends approximately $13 million annually in roadside litter clean up.”5 On average, Philadelphia uses approximately 1 billion plastic bags each year, and it costs the city between $7 and $12 million dollars to remove them.6 New York City has similar numbers on an annual basis: “single-use, carry-out bags account for 1,700 tons of residential garbage each week, which equates to 91,000 tons of plastic and paper carry-out bags each year and presently costs the City $12.5 million annually to dispose of this material outside the city.”

Nationally, cities, towns, and businesses pay roughly $80 a ton for single use plastic bags to either be buried in landfills or be incinerated, both actions have high externality costs associated with them.7 Hypothetically, if we were to apply this figure to Easttown Township, we are roughly 1/800th the size of New York City and thus produce approximately 114 tons of plastic and paper carry out bags each year, or $9,120.00 in disposal costs.

Another major way single use plastic bags prove economically burdensome is for recycling facilities. “Single use plastic bags are the number one contaminant found in recycling facilities, clogging machinery and decreasing the efficiency of recycling programs in Pennsylvania that are often already struggling.”8

The extent of this problem can be demonstrated in San Jose CA, which spent nearly $1 million per year on repairing plastic bag related damages. In a similar case, a recycling factory had to close down up to six times a day in order to remove the trapped plastic bags in the machinery.” Several recycling facilities in NY have estimated costs associated with extra operational costs for removing single use plastic bags from their lines between $300,000 to $1 million per year.9

Beyond the local economic impacts, plastic pollution costs $13 billion in economic damage to marine ecosystems per year. This includes losses to the fishing industry and tourism, as well as the cost to clean up beaches.10 This includes local beaches like the Jersey Shore, where twice annual clean ups remove litter from the beaches and accessible waters. In 2017, 84% of the material collected was plastic or foam plastic and 66% of that number was of the single use variety including single use plastic carry out bags. On average, residents of coastal areas spend $15 per year to clean up their beaches in taxes.11

Finally, a cost-benefit analysis of the proposed plastic bags ban would be incomplete if the incalculable environmental damages caused by single use plastic bags was not mentioned.

Single use plastic bags are a petroleum product; they require 12 million barrels of oil annually to produce, equating to 4% of the world’s annual oil budget.12 The emissions associated with producing plastics will exceed those from burning coal by 2030.13 The economic costs of these emissions at the global level are unknown but the impacts to climate change and air pollution are considerable and long lasting. The Equinox Center in San Diego calculated that a plastic bag ban and fee model similar to the one proposed in Easttown Township would reduce San Diego’s energy (74 million Megajoules (MJ)), CO2 footprint (6,418 tons) and solid waste (270,000 kg) on an annual basis.14 Again, if we were to use these calculations at a per capita basis for Easttown, this would hypothetically equate to a CO2 footprint of 19.7 tons and 831 kg of solid waste for the Township.

Beyond global energy and emissions constraints, the major environmental risk posed by single use plastic bags is their inability to decompose. Over time, plastics degrade to smaller microplastics that can be ingested by the smallest species at the base of our aquatic and terrestrial food webs. Ultimately, limiting single use plastics in the food web limits our own intake of plastics from our food and water sources.

In summary, plastic bag bans reduce all these costs for municipalities, costs which are passed on to residents, by reducing the amount of plastic pollution and waste we need to handle. For businesses the impact is that a plastic bag ban with a fee on other bags reduces overall single use bag use. With less demand for bags, businesses don’t need to purchase and stock as many bags, saving them costs. And although paper is more expensive than plastic, having a built-in fee for paper bag covers the difference, so businesses don’t need to pay more.

Easttown Township has an opportunity to be one of the first local municipalities to pass an ordinance of this type and help push the envelope for our community.

1 “Plastic Bag Bans: Analysis of Economic and Environmental Impacts”. Equinox Center. Oct. 2013. https://energycenter.org/sites/default/files/Plastic-Bag-Ban-Web-Version-10-22-13-CK.pdf /.

2 Savitz, Faran. Email correspondence reg. economic benefits of a bag ban. Google. Mar. 2022.

3 Plastic Bag Ban Information Session #2 for Delaware County, PA. Logan Welde, Clean Air Council, 2/8/2022.

4 “Looking to Cut Plastics pollution in the ocean? Start upstream.” Jamarillo, Catalina. Jul. 2018.

5 Savitz, Faran. Email correspondence reg. economic benefits of a bag ban. Google. Mar. 2022.

6 Keep Pennsylvania Beautiful. “Litter & Illegal Dumping in Pennsylvania: A study of nine cities across the commonwealth” Jan. 2020. https://www.keeppabeautiful.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/KPB-Litter-Cost-Study-013120.pdf/.

7 “An analysis of the Impact of Single Use Plastic Bags. Options for the New York State Plastic Bag Legislation.” New York State Plastic Bag Task Force. Jan. 2018. https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/materials_minerals_pdf/dplasticbagreport2017.pdf/.

8 Savitz, Faran. Email correspondence reg. economic benefits of a bag ban. Google. Mar. 2022.

9 “An analysis of the Impact of Single Use Plastic Bags. Options for the New York State Plastic Bag Legislation.” New York State Plastic Bag Task Force. Jan. 2018. https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/materials_minerals_pdf/dplasticbagreport2017.pdf/.

10 “Plastic Waste causes $13 billion in annual damage to marine ecosystems, UN Agency says” United Nations. Jun. 2014. https://news.un.org/en/story/2014/06/471492-plastic-waste-causes-13-billion-annual-damage-marine-ecosystems-says-un-agency/.

11 “Looking to Cut Plastics pollution in the ocean? Start upstream.” Jamarillo, Catalina. Jul. 2018, https://whyy.org/segments/looking-to-cut-plastics-pollution-in-the-ocean-start-upstream/.

12 “Plastic Bag Bans: Analysis of Economic and Environmental Impacts”. Equinox Center. Oct. 2013. https://energycenter.org/sites/default/files/Plastic-Bag-Ban-Web-Version-10-22-13-CK.pdf/.

13 Plastic Bag Ban Information Session #2 for Delaware County, PA. Faran Savitz, PennEnvironment, 2/8/2022.

14 “Plastic Bag Bans: Analysis of Economic and Environmental Impacts”. Equinox Center. Oct. 2013. https://energycenter.org/sites/default/files/Plastic-Bag-Ban-Web-Version-10-22-13-CK.pdf/.

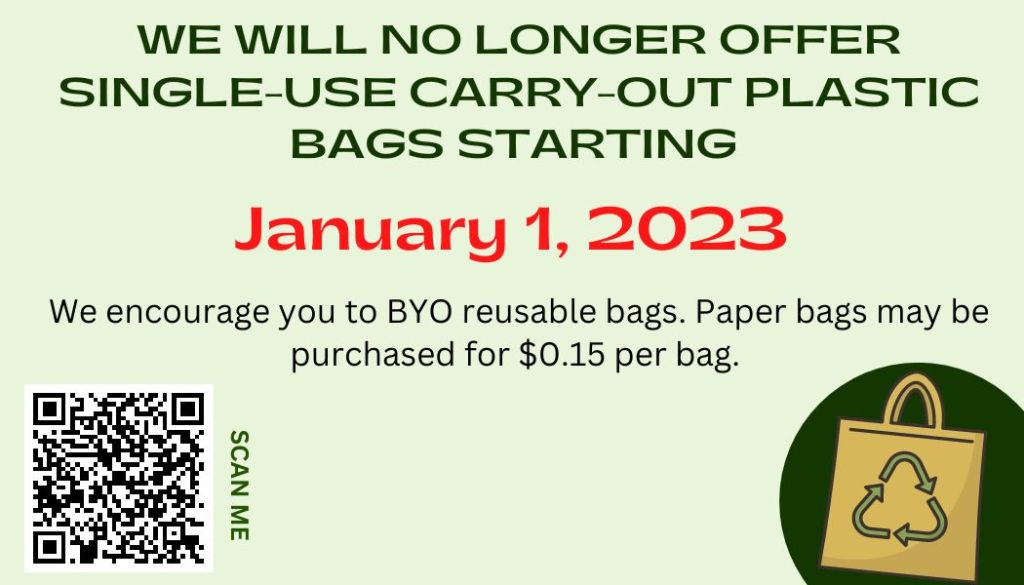

The Easttown Plastic Bag Ban

On January 1, 2023, Easttown’s ban went into effect. You can find a comprehensive FAQ page on the Easttown site. Download the 2-sided pdf designed for commercial establishments here.

Click here for the text of Easttown’s very useful and well-footnoted 2022 “Economics of Single Use Plastic Bags” document, showing how—alongside the environmental benefits, of course—retailers, recycling facilities and municipalities gain financially from a reduction in plastic waste. Here are the concluding paragraphs:

…Beyond global energy and emissions constraints, the major environmental risk posed by single use plastic bags is their inability to decompose. Over time, plastics degrade to smaller microplastics that can be ingested by the smallest species at the base of our aquatic and terrestrial food webs. Ultimately, limiting single use plastics in the food web limits our own intake of plastics from our food and water sources.

In summary, plastic bag bans reduce all these costs for municipalities, costs which are passed on to residents, by reducing the amount of plastic pollution and waste we need to handle. For businesses the impact is that a plastic bag ban with a fee on other bags reduces overall single use bag use. With less demand for bags, businesses don’t need to purchase and stock as many bags, saving them costs. And although paper is more expensive than plastic, having a built-in fee for paper bags covers the difference, so businesses don’t need to pay more.

Model handout for Easttown retailers:

CCEA Common Environment Agenda

CCEA’s 26-page Common Environment Agenda (click here), presented to the County Commissioners in 2022, contains many valuable recommendations.